Introduction

The head is probably one of the most difficult things to sculpt when it comes to horses. You gotta admit, its many planes, angles, symmetries, and skeletal and fleshy structures offer a continual challenge to even the most seasoned sculptor. Indeed, there's a lot going on in a relatively small space! That being the case, we can get confused and go off track even with the most painstaking diligence or even worse, become quickly overwhelmed and frustrated. And as humans who are visually oriented and sensitive to facial cues, we naturally zero in on the head immediately. If something is off then, that error can become rather distracting and compromise what else we’ve gotten right. Luckily though there are some basic measurements we can use as guides, as neutral baselines we can use to sculpt any equine head with relative ease. And by providing a straightforwards architecture, a framework that directs our sculpting, we gain more clarity and direction in what we’re doing. Even better, these baselines are universal regardless of the breed, species, expression, or individual and so we can apply them across the board to express any characteristic or eccentricity we wish.

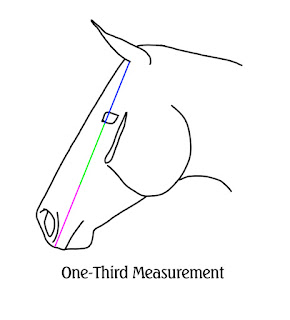

Simply put then, I use eleven basic guidelines for sculpting any equine head. Just remember though that these guidelines should be used as a starting point from which to build those unique features your piece needs. In other words, think of these as starter guidelines you’ll need to tweak as needed, they aren’t dogma. But we have to start somewhere, right? Now to big picture it all, the most important measurement is the total head length, from the back of the ears at the poll to the end of the (un-pooky) upper lip. It’s from this measurement that most of the others derive, which can be broken down into one–half, one–third, and one–fourth increments for the most part. From those we can finagle our way to greater precision because they give us a consistent place to start. So what are these basic guidelines? Well, let’s just jump right in!…

Get In Line

The Ears–Eye–Nostril Alignment (EENA) is a fundamental, very important guideline and lucky for us, it’s easily gauged with a straight edge like a pencil, ruler, a paintbrush, or the long side of calipers. Why is it so important? Well, for one it establishes the length of the head from which we derive a lot of our other guidelines. And for another, it helps us to place our ears, eyes, and nostrils. And lastly, it determines the axis of the head whether straight, convex, or concave. So going from the bottom of the ear bulb, under the bottom of the eye and then to the bottom of the nostril, we can see how they tend to line up. However, keep in mind that the illustration is of a straight head, which is why they line up. For instance, many Thoroughbreds, Warmbloods, Saddlebreds, Mustangs…many horses…have a more or less straight alignment to the EENA, or a straight head. There’s a bit of variation, of course, but for the most part, many horses line up to a straight EENA pretty well. In contrast, sometimes this axis can be bent upwards, or convex, with the nostril dipping below the line a bit as can may see with breeds with a convex profile such as many Iberians, Campolinas, Kladrubers, some drafters and such. In contrast, sometimes this axis can be bent downward, or concave, with the eye lying just below this line. This kind of head can sometimes be seen with some Arabians, in particular, or other “dishy” heads. But this is why carving in a dish or simply adding a roman nose often doesn’t always create such a convincing head type because we aren’t addressing the actual axis of the skull.

What’s more, notice that the teardrop bone (or facial crest) somewhat parallels the EENA, too, a handy observation for shaping our head. The line of the mouth can as well at times. Regardless, use the EENA to study lots of different heads to get an idea of all the consistencies as well as all the variety and options involved — there’s a lot!

Three Times The Charm

I’m All Ears

Spread Out

Now determining the width of the head, the distance between the brows, can be quite tricky as it varies a lot between individuals, breeds, and species. For example, some Iberians, drafters, and Saddlebreds can be rather narrow whereas others like the Arabian, Morgan, and some ponies can be quite broad. Field study is your best bet here, taking actual measurements from lots of real horses to get a bubble of options. But you can also study lots of reference photos from different angles, especially from the front, though this is much trickier.

Even so, a good start is a measurement about one–third the length of the head, between the front canthi. Then we can make it narrower or wider as the sculpture requires.

As for the width of the jowls, that varies a lot, too, especially between breeds. For example, stock horses can have very wide, hefty jowls, even extending beyond the width of the teardrop bones. Nevertheless, we can start here as a baseline: The width of the jowls ballparks about one–half of the head length.

The width of the cheeks, the area between the jowls and muzzle, is often comparatively narrow, sometimes markedly so. So to get us started, think of this area as being between one-third to one–fourth the length of the head or thereabouts, adding or subtracting width as we need to for our sculpture.

The width of the muzzle can vary a lot as well, being quite broad or quite narrow, and everything in between. This is also where field study and references photos of a straight on front view are so useful. Nonetheless, we can think of the width of the muzzle as about one–fourth the length of the head, adding or subtracting width as needed for our piece.

Flare Up

Nostrils can be a tricky thing to sculpt owning to their fleshiness and pliability. They can certainly squinch to become narrow and pinched one moment to then become wide and cavernous the next. So here’s where field study and reference photos are particularly helpful, especially since all this needs to be synched to the level of exertion, the communication, or the mood depicted by our sculpture.

Even so, we can think of a resting nostril as a baseline and even though that varies between individuals, breeds, and species, we can make a couple of general starter observations. For one, the length of a typical nostril is about one-eighth the head length from the upper “V” to the bottom of the posterior rim at rest. On the other hand, when flared, that proportion will expand to open up the nostril to varying amounts. What’s more, certain breeds like Arabians and Thoroughbreds should have large standing nostrils as a point of type.

Mouthing Off

For a starting point, sometimes the angle of the mouth is rather parallel to the EENA, similar to the teardrop bone. Of course, there’s going to be variations, but again, this gives us a good place to start our investigations. As for length, we can think of the mouth as being about as long as where the chin connects to the lower jaw, give or take depending on the individual, breed, or species. In fact, some breeds ask for a longer mouth, such as the Arabian.

As a general tendency, too, the front “corners” of the lower lip tend to protrude a bit past the front portion of the upper lip but the lower lip tends to be more depressed inwards at the corner of the mouth. This isn’t always the case, but we can use this tendency to find variations.

Bar None

The length of jaw bars from the intersection with the jowls to the edge of the chin varies a lot, but a good baseline is this can sometimes be just over one-third the head length. Study this a lot between individuals, breeds, and species to find all the fun options for your sculpture.

Wearing The Crown

The width between the ears, or the crown, also varies a lot between individuals, breeds, and species so study this a lot, too. Like generally speaking, Arabians and Morgans can be quite wide in the crown whereas Iberians, Saddlebreds, and some drafters can be relatively more narrow. As a basic measurement to make adjustments from though is that the crown can be somewhat one-third the head measurement from the bottom “v” fold of ear to ear.

Dem Peepers

One feature of the head that’s quite variable is the size of the eye — not the orb itself, but the eye as measured within the surrounding lids from the front canthi to the back canthi. So do a lot of study here to find your options. For instance, Arabians and many ponies tend to have bigger eyes than say drafters or Warmbloods due in part to the structure of the surrounding fleshy features and relative head size. As a general idea though, the typical eye is about one-twelfth the length of the head, give or take, so make your necessary determinations from that point. A common hiccup when sculpting the eye, as a function of artistic stylization, is to make the eyes way too big so this measurement can be really helpful to avoid this.

Spinnin’ Out

The canthi (the front and back corners of the eye) of the typical eye are angled to the EENA at about 40° - 42°. There’s individual, breed, and species variation, of course, but this is a good starting point to make your adjustments.

Life study and references can provide a good mental library. But getting this angle is important because if the canthi are angled improperly, if they’re spun out of alignment, the head will look odd.

Ending Thoughts

See, once you have some basic guidelines, putting together the rest of the noggin isn’t so hard! The trick is just doing your homework ahead of time so you know how to tweak these measurements and alignments when it comes time to sculpt. Preparation is key! It’s also important to use these guidelines to study lots of individuals, breeds, and species so you can develop a solid mental library of the possible options. Honing our Eye will always serve us well. And just as much, regularly checking our work against these measurements as we sculpt will keep our work from going sideways which can happen if we lose sight of the big picture. And above all, practice practice practice! If you can draw, do lots of sketches. Do some quick maquette work in non-hardening clay like Sculpey or oil clay. Look at your sculpted head in a mirror to freshen your eye with a "reversed" view. Take pictures of your sculpture and check your work within the objectifying lens of the camera for another fresh eye, reversing it too in a photo editing program for another view.

Every horse has a unique head, just like us. How cool is that? So many potential options! So as realistic equine artists, the better we can create a basic head and the better we can pinpoint where to tweak it for individual variation, the better and more varied our heads will turn out. Overall then, learn to apply these guidelines as standard operating procedure and pretty soon they’ll become second nature and you’ll find yourself not only having an easier time sculpting heads, but be better able to pinpoint what’s so wonderfully different between them all! What a great way to get ahead!

“This world is but a canvas to our imagination.”

— Henry David Thoreau